by Brian Olewnick

Every so often, more so in recent years, a release passes across my desk and through my ears whose contents consist of unadulterated, unprocessed field recordings. Now, I have, I daresay, hundreds of recordings that utilize field recordings to one extent or another but even those wherein the entire contents are sounds picked up by a mic left out in the desert or beside a highway or within the hull of an old boat generally involve some degree of manipulation by the person involved, some sculpting, some design element. These can, in the right hands, be extraordinarily beautiful documents. I'm thinking of Toshiya Tsunoda's "Scenery of Decalcomania", for example. The choices he makes, the weight he assigns to the various elements work to create a composition which seems for all the world to be "just" a recording of a scene but, in fact, is an idealized situation, a fictional world more incisively etched than what you're likely to hear yourself, as a blank wall by Vermeer contains more in it than you're likely to see, looking straight into one.

Tom Lawrence's "Water Beetles of Pollardstown Fen" (Gruenrekorder) is a set of ten recordings of just that, as well as a good deal of plant life. All of the sounds--and there's an impressive variety of them--were recorded beneath the surface of the water, the mic often positioned quite close to the stridulating insect. The sounds are reasonably fascinating--how could they not be?--all clicks and whirs and guttural buzzes and whines, sometimes possessing an eerily human quality, like a covey of muttering old crones or some guy iterating a brief, pained cry. It's certainly a world unobtainable by ones even were one to immerse head in fen so there's a certain value having been exposed to it as all. The question is, is that value one of a purely educational or scientific sort and, if so, how to deal with it when presented as "art". There's also the issue, beautifully recorded though it may be, of how much is lost hearing these sounds issue from two speakers; if nothing else, the reality is a surround-sound experience. How to evaluate? Try as I might, I can't really rate this water scorpion's croak over that Great Diving Beetle. No reason to, of course, but after a listen or perhaps two, what does one derive from this. I now have some idea of what the insect life in this fen and, by extension, other small bodies of water, may tend to sound like which is all well and good, but am I going to go back to this to refresh my memory? In all likelihood, no. Unlike the example given above, the Tsunoda, I don't think there will be layers to continue to peel away, relationships to discover for the simple reason that there's not a human decision maker, at least not one making decisions of much import aside from track length. Or perhaps decisions were in fact made and the hand that made them lies a bit heavy, smoothing the sounds into a kind of sheet that, for all its wealth of sounds, carries with it a kind of sameness, a sameness that I very much doubt would be heard in situ, where one would be making his/her own decisions on how to listen, on how to balance the rich, subaqueous sound world. Somehow, something essential seems lost in the translation to disc, more so than is, of course, always the case with music transferal generally.

Eisuke Yanagisawa's "Ultrasonic Scapes" offers a case that is, in one sense, at an opposite end of things but in another, comes up against the same problem. He uses a bat detector to makes his recordings. One track, indeed, depicts bats while another goes after a choir of cicadas but the majority, eight out of ten cuts, pick up the faintly heard, to human ears, sounds of the industrialized world, including electric gates, street lights, muted TVs and computer innards. As with Lawrence's disc, one is privy to sound environments normally hidden from, um, view although in this case, one imagine that, given a quiet enough space and the desire to do so, one could discern a good bit of it. But again, it's presented "as is", without manipulation or intent save for determining track length. Are the sounds interesting? Sure, for the most part, all of them, I suppose. Are they more interesting than what I can hear almost any time I want by merely concentrating on what happens to be within range? I'm not so sure. Granted, bats and cicadas aren't flitting about at the moment, and the intensity level is pretty high here but I think we've all enjoyed a good refrigerator hum, savored the ultrasonics emitted when the TV is muted. I'll be on a ferry this weekend and fully intend to lean up against the engine housing, letting the dull roar vibrate ears and body. The awareness of all the sounds around us which, surely, we've all been practicing to one extent or another at least since finding out who this John Cage feller is, makes experiencing a similar set of sounds through speakers a somewhat diluted event. Not only is, unavoidably, a good bit of spatial resonance lost but, as mentioned above, one feels a bit coerced down the recordist's chosen path. It's one thing, perhaps, to be so led in the course of a composed or improvised piece of music, another when it's something apart from the person making the delivery. You'd somehow like to be introduced to an area, then let alone to discover things on your own, an impossibility, I guess, given existing technology.

This is not to say that either recording isn't worth listening to. They are, in a way (The Yanagisawa more so than the Lawrence, to these ears), even if they leave me with an extremely unsatisfied sensation. They both succeed, as near as I can do, with doing what they set out to and do so admirably and attractively but I can't shake the feeling that I'd rather dip my ear in a pond or press it up against a street lamp myself.

Gruenrekorder

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

Monday, July 18, 2011

Derek Bailey: More 74

Derek Bailey

More 74

(Incus)

by Kurt Gottschalk

Any discovery of a tape box with Derek Bailey’s name on it is something to be heralded. He was an unequivocal champion of improvisation as instinct, not genre (and certainly not merely “jazz”), and an absolute iconoclast on his instrument. If all artists were as intent on upending the context within which they exist, we likely wouldn’t be able to tell paintings from pantomimes.

Debilitation eventually quieted his sonic quest, and unearthed recordings have been surprisingly few since his 2005 death, but the discovery of unreleased tapes from the sessions that produced his 1974 record Lot 74 is a fantastically welcome surprise. That album — released early in his recording career (and issued on CD in 2009 by Incus, the label he co-founded) — caught him in his most overtly experimental period. Following the two volumes of Solo Guitar, Bailey set out to expand his instrument. With two leads coming off his guitar, running to separate volume pedals and separate amplifiers, he was able to create an electrified, stereo field. His utterly enigmatic plinks and clusters and harmonics and muted strings pan back and forth to dizzying effect.

He plays the “stereo electric guitar” on all but the last seven minutes of More 74, the CD issue of that discovered tape reel, and as terrific as the tracks are, they are outtakes. Many of them are under five minutes, and there is included — rather fascinatingly — a few alternate takes of tracks Lot 74. What is perhaps most wonderful about getting a fresh listen to his electric set-up, though, isn’t how radically different he sounds but how much the same. The rig allows for more exaggerated gestures, but the style is familiar, and in fact was remarkably consistent throughout his recording career. It’s as if, having heard the attack and delay and convergences of dually amplified strings, he soon returned to acoustic playing to chase those same sounds.

The final seven minutes of the disc are performed on a more curious device from Bailey’s days of axe modification, an instrument he called the “19-string (approx.) acoustic guitar.” It’s a sort of manic, harp-like thing, with constant detuning a rattling, but again sounds remarkably like him. The program closes with a track called “I Remember the Seventies,” a stab (assumedly the first) at what is called “In Joke (Take 2)” on Lot 74. Here he looks back on what was then the current day, not accompanying himself in a customary sense but playing jaggedly while speaking, as he did on his later Chats records. The piece is delivered with no undue irony, just a nice touch of absurdism, as he recalls his contemporaries in an economy of verbage. It is a happy eventuality that 37 years later, we get to remember again.

More 74

(Incus)

by Kurt Gottschalk

Any discovery of a tape box with Derek Bailey’s name on it is something to be heralded. He was an unequivocal champion of improvisation as instinct, not genre (and certainly not merely “jazz”), and an absolute iconoclast on his instrument. If all artists were as intent on upending the context within which they exist, we likely wouldn’t be able to tell paintings from pantomimes.

Debilitation eventually quieted his sonic quest, and unearthed recordings have been surprisingly few since his 2005 death, but the discovery of unreleased tapes from the sessions that produced his 1974 record Lot 74 is a fantastically welcome surprise. That album — released early in his recording career (and issued on CD in 2009 by Incus, the label he co-founded) — caught him in his most overtly experimental period. Following the two volumes of Solo Guitar, Bailey set out to expand his instrument. With two leads coming off his guitar, running to separate volume pedals and separate amplifiers, he was able to create an electrified, stereo field. His utterly enigmatic plinks and clusters and harmonics and muted strings pan back and forth to dizzying effect.

He plays the “stereo electric guitar” on all but the last seven minutes of More 74, the CD issue of that discovered tape reel, and as terrific as the tracks are, they are outtakes. Many of them are under five minutes, and there is included — rather fascinatingly — a few alternate takes of tracks Lot 74. What is perhaps most wonderful about getting a fresh listen to his electric set-up, though, isn’t how radically different he sounds but how much the same. The rig allows for more exaggerated gestures, but the style is familiar, and in fact was remarkably consistent throughout his recording career. It’s as if, having heard the attack and delay and convergences of dually amplified strings, he soon returned to acoustic playing to chase those same sounds.

The final seven minutes of the disc are performed on a more curious device from Bailey’s days of axe modification, an instrument he called the “19-string (approx.) acoustic guitar.” It’s a sort of manic, harp-like thing, with constant detuning a rattling, but again sounds remarkably like him. The program closes with a track called “I Remember the Seventies,” a stab (assumedly the first) at what is called “In Joke (Take 2)” on Lot 74. Here he looks back on what was then the current day, not accompanying himself in a customary sense but playing jaggedly while speaking, as he did on his later Chats records. The piece is delivered with no undue irony, just a nice touch of absurdism, as he recalls his contemporaries in an economy of verbage. It is a happy eventuality that 37 years later, we get to remember again.

Sunday, July 10, 2011

Michael Mantler - The Jazz Composer's Orchestra

Biographical details regarding Michael Mantler seem to be fairly scarce. Trawling about on-line, we see that he was born in Vienna in 1943, began playing trumpet at 12, worked in dance hall bands from the age of 14 and, in 1962, immigrated to the US to study at Berklee, an experience he apparently found uninspiring. He moved to New York in 1964, quickly hooking up with musicians involved in the “October Revolution in Jazz“ and, in particular, with Carla Bley, forming a personal and musical relationship that lasted until 1992. The pair formed the Jazz Composer’s Orchestra in 1964, and also the Jazz Realities Quintet which, at various times, included Steve Lacy, Peter Brötzmann, Kent Carter and Peter Kowald.

His first release, from 1965, already bore the title, “Communication” and featured a hefty collection of musicians including Archie Shepp, Steve Lacy, John Tchicai, Paul Bley, Jimmy Lyons, Roswell Rudd and more. The music shows glimmers of things to come or larger aspirations perhaps, but is more a mass of somewhat exciting, somewhat muddled improvisation, very loosely molded along vague structures. I’m not at all sure what transpired in the ensuing three years, whether or not Mantler acquired any formal training in orchestration (whether he ever had any at all, in fact, of if he was self-taught, which it sometimes sounds like), but whatever the case, by the time he was 25, his conception had matured and blossomed into an astonishing creature.

The first album under the JCOA imprint was a two-record set that arrived in a gleaming silver box bearing the simple title, “The Jazz Composer’s Orchestra”, followed by a listing of the principal soloists, Cecil Taylor’s name separated from the rest: Don Cherry, Roswell Rudd, Pharoah Sanders, Larry Coryell and Gato Barbieri. Along the bottom, read, “Music Composed and Conducted by Michael Mantler”. Inside was a 12 x 12” booklet bearing track information, photos, scores, an excerpt from Beckett’s “How It Is”, a two-page poem by Taylor and texts by Paul Haines and Timothy Marquand. The pieces once again, with one exception (“Preview”), bore the title, “Communications”, here numbered 8 through 11. Looking at the instrumentation, we still see what is essentially a jazz big band, larger than the prior recording (over 20 musicians) and notable for the presence of five bassists. The sound generated, however, was orchestral.

It was a wonderful idea, one borne partly of the time but not really followed through anywhere else to the degree heard here, much less with similar success: Compose works for a band of extremely talented musicians that fused a kind of dark, brooding Romanticism, as though Arnold Böcklin’s vision was filtered through Mahler by way of Beckett, all exposed to the protean strength and creativity of 60s free jazz. Within this dense mix, position soloists whose voices emerge from the roiling darkness as brilliantly faceted jewels, unleashed from the group but gravitationally pulled back into it. Add to this the serendipity of the chosen soloists being at or near the height of their powers and you have the recipe for one incredible stew.

An obvious key to the success of these works is the dense, sprawling orchestration that Mantler laid down behind the soloists—“behind” isn’t the correct term as the music writhes and gropes, sending out thick tendrils that envelop the featured musicians, never allowing things to atrophy into a soloist/accompaniment form, but keeping things, for lack of a better term, extraordinarily organic and plastic. As the first track, “Communications #8” begins, the orchestra wells up, already seething, sounding somehow more “orchestral” than jazz-bandish despite the instrumentation (the massed basses might be a contributory factor). Mantler’s score-notes for the piece: “For a team of players. Loosely strung. Much singing. Release. A long descent.” The long, brooding tones are routinely disrupted by more staccato passages, Bley’s spiky piano ameliorating any smooth flow, the whole jittery and dark before Cherry’s clarion pocket trumpet enters. Cherry, in the late 60s, to these ears, reached an astonishing peak of melodic inventiveness, doubtless inspired by his absorption of Eastern musics, though transformed into something very unique (see: “Eternal Rhythm”). He negotiates a path through the maze of strings and horns, graceful but not a little tragic. Again, crucially, he’s on equal footing, not in front of the orchestra but within, a single mass. Then the fire-breathing Barbieri enters, full force, ripping through his tenor, himself having entered a period of unfettered creativity that would carry through to “Escalator Over the Hill” and “Tropic Appetites” before fame and final tangos ensnared him. But he’s so strong here, soon entwining with Cherry, plaintive and vital Cherry, forming a complex vine of sound, whirling through the arrangement, the tubas and French horns darkly billowing, Cyrille driving the ensemble with abandon. And the long, not unruffled descent.

“Communication #9” (“About the weaving of clusters. The natural electric orchestra. The amplifier.”), oddly enough, might be the “weakest” piece here at the same time as it could be the finest thing Coryell ever recorded. I remember reading an interview with Coryell a long while back wherein he expressed his frustration that every time he’d make what he thought was a significant advance in pushing forward the possibilities of the electric guitar, he’d soon find out that Hendrix had beaten him by a few months. Well, here in May of ’68, he’s certainly pressing at boundaries, at least those walls set up in the galaxy apart from Rowe and Bailey. The orchestration is sparer, piano and high string harmonics supporting quietly harsh brass that feed directly into the initial feedback-laden guitar. Photos from the session show Coryell engaged in a wrestling match, his guitar vs. the amp; perhaps half of his time here is spent wringing feedback from his axe, a bit more up front than were Cherry and Barbieri, and maybe indulging, in this context, in a tad more flashy playing than necessary, but nonetheless impressive.

Steve Swallow’s gorgeous, questioning bass introduces “Communications #10” (“Expansion. The exquisite low horn”), worth the price of entry on its own, before the elegiac reeds and brass, evocative of some of Carla Bley’s writing, usher in the body of the piece, again laying a substantial bed, open to and full of possibilities from which the featured player emerges, here Roswell Rudd, his natural buoyancy spiced with no small amount of mordancy and even the tinge of despair. Beckett is never far from Mantler’s conception.

“to have done then at last with all that last scraps very last when the panting stops and this voice to

have done with this voice namely this life.”

Rudd trends toward his horn’s lower reaches, bringing forth guttural shouts from the surly orchestral growls. As with the others, it’s difficult to think of a finer, more expansive performance from him, as though Mantler had provided exactly the right framework and accompaniment, especially Beaver Harris here, on drums.

And then there’s “Preview”, a 3:23 blast furnace attack with white hot slag erupting from the bell of Pharoah Sanders’ tenor over the incessant, almost martial throb of the orchestra. No let up, start to finish, one of the mostly densely packed, insanely ecstatic performances on record, something guaranteed to send the neighbors fleeing in alarm. Has Sanders ever sounded this volcanic elsewhere? Is there another example where concision and raw power are so perfectly combined? An exhausting, astonishing work.

And, really, it proves to be only a stage-setter, an appetizer for what follows: about 33 minutes, in two sections, of some of the music incredibly inventive and dynamic Cecil Taylor playing ever caught on record, “Communications #11”. (“From the association with one man. The orchestration of his piano.”) I remember reading the review of this piece in downbeat, the writer explaining that he felt the need to glance over at his stereo to ensure that the LP wasn’t levitating off the turntable. It really is that strong, protean, a living, throbbing, hyper-imaginative set of music with the wonderful happenstance of Mantler’s ideas blossoming at the exact moment Taylor was making the transition in his playing from the fevered hermetics of his two mid-60s masterpieces, “Unit Structures” and “Conquistador!” into the elaborate and expansive explorations that would soon be heard in works like “Indent” and “Silent Tongues”. Trying to describe it is something of a fool’s errand anyway; I’ve often had the mental image of a cauldron containing molten metal, boiling, sustaining a plosive pattern somewhere between regularity and chaos. Unlike many a “pairing” between Taylor and a playing companion where the pianist all but overwhelms his ostensible partner, the orchestra gives as good as it gets, spurring him outward. It’s an avant piano concerto that indeed nods back to a kind of Mahlerian tonality while giving Taylor free rein to pull it toward the 21st century. An utterly breathtaking work, successful on multiple counts and a high water mark in Taylor’s career.

At least that’s my take on it; one wonders about Mantler’s. He never really broached this area again, with the arguable exception of his monolithic and extremely impressive “13” from 1975, which shared an LP with Bley’s beguiling and lovely “3/4”, itself a piano concerto of sorts but in a far lighter vein. Otherwise, he tended to work with smaller ensembles, early on notching a couple of outstanding one-offs, “No Answer”, a setting of Beckett text with Cherry, Bley and Jack Bruce and “The Hapless Child”, a prog-rockish rendition of several Edward Gorey poems featuring Robert Wyatt, Terje Rypdal and others. He continued to utilize Beckett and like-minded writers and his work became even bleaker, often intriguing but, to these ears, lacking that unique combination of latent Romanticism to leaven the dourness; there was no Cecil Taylor to provide the ecstatic leaps from the muck. If anyone picked up the torch, one would have to cite Barry Guy with his London Jazz Composer’s Orchestra, albeit with a necessarily different personal tinge and, arguably, a level of soloist one tier below these fellows here (while still excellent).

Yet I don’t hear this recording, this set of “Communications”, discussed very often and think it’s a shame. For this listener, it stands as one of the very finest creations of the 60s jazz avant garde and deserves far wider recognition.

--Brian Olewnick

--Brian Olewnick

Monday, July 4, 2011

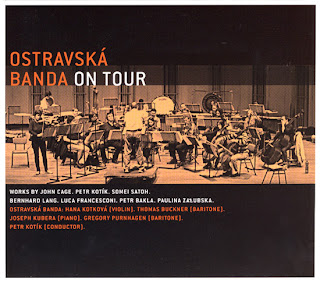

Ostravská Banda: On Tour

Ostravská Banda

On Tour

(Mutable)

by Kurt Gottschalk

The versatile 20-piece Ostravská Banda might be seen as a cultural-ambassador assembly for the biennial Ostravská Days festival, a growing part of the Czech Republic's new music landscape. Initiated in 2001, the festival is dedicated to contemporary orchestral works. In 2005, the Banda was founded by SEM Ensemble conductor Peter Kotik to give the festival its own standing orchestra and to create a touring body to represent the work.

The seven compositions presented over the two hours of the double CD On Tour were recorded in 2010 at appearances in Poland, Austria, the Netherlands and the Czech Republic. The program represents some pillars of 20th Century composition as well as – can we call it post-20th Century music, the patron saint being, unsurprisingly, John Cage, and the ensemble presents a challenging reading of his Concert for Piano and Orchestra. The piece comes with a Czech footnote: While it allows for variable instrumentation, it was only in Prague in 1964 that he was able to give the first full presentation of the piece following its 1958 New York premiere. The piece is constructed (as is true with so many of Cage's works) in time intervals, with allowable events for individual instruments – scored or suggested sounds – happening within the time brackets. The featured pianist is given the most complex part, with a book of 64 one-page scores from which to choose.

With the talented American pianist Jospeph Kubera at the fore, the piece is given a dramatically disparate performance – appropriate for the work, even if it is surprising give the fullness of the rest of the tracks. Musical gestures don't fall together, they just occur, as famously is the composers intention. The orchestra recedes to the background as the piano – bright and abrupt – dominates the soundspace. The noncohesivesness becomes a richness in field over its 23 minutes, something the composer no doubt would have appreciated.

That piece starts off the second disc of the set, and is followed by Kotik's 2009 composition In Four Parts [3, 6 & 11] for John Cage. It's a tightly constructed homage to the earlier composer's first love, percussion music, and is a taut and dynamic 24 minutes – so much so that it leaves Bernhard Lang's 2008 percussion piece Monadologie IV in its shadow. As opposed to the rigors of Kotik's piece, the Monadologie comes off as a sort of exploded drum solo, that is, more showy than satisfying. Thirty-six minutes of percussion music might be a bit much for some listeners, and it does make for a diminished finale.

The first half of the set opens with a wonderfully romantic flourish. Luca Francesconi's 1991 Riti Neurali follows (as the liner notes point out) the instrumentation of Schubert's Octet in F Major, although it speaks in the dramaturgy of Schoenberg; The violin-dominated flurry is exhilarating. While Francesconi studied under both Berio and Stockhausen, here he speaks in a language of measured atonality and straightforward passion.

That piece is followed by two works by young composers, both vivid and exciting, and quite different from one another. The 31-year-old Petr Balka's Serenade is a wonderful construction of differing tonal qualities. Bold outbursts are laid over quieter and sometimes fairly simplistic phrases in unexpected ways, creating a tableau of phrases with the energy of potentiality, of what the composer calls “not-quite-yet-music.” The 27-year-old Polish composer Paulina Zalubzka works with varieties of lyricism reminiscent in ways of both the Francesconi and Bakla pieces in her Dispersion, its persistent rhythm moving in and out over unabashedly beautiful passages.

The only non-Western composer present here is the Japanese Somei Satoh, represented by a half-hour “reduced setting” of his The Passion. With inventive use of a male choir and strong performances from baritones Thomas Buckner and Gregory Purnhagen. The piece is just beautiful, an unusual juxtaposition of minimalist gesture and rich harmony.

The impetus behind producing such a strong and varied package as On Tour may or may not have been to serve as a calling card for the ensemble and, by extension, the festival. But either way, the point is well made.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)