by Kurt Gottschalk

Dylan Carson has fronted his band Earth (if with a good number of membership changes) for a remarkable 22 years, and in the process has outlined something of a continuum of heavy rock. Although the band came out of the Seattle grunge explosion, their doomy, downtempo riffs stem from a moment predating grunge, predating punk and predating the New Wave of British Heavy Metal. Carson reached further back, lifting Black Sabbath's original name and borrowing from that band's early metal inventions. But the glacial power Carson has crafted over the course of a dozen albums is hardly a throwback. His revelation wasn’t just in tempo, it was in taking the posture of hard rock and freeing it from the constrained expectations of heavy metal. And as such, Earth has been the impetus for the most exciting new movement in rock since Carson was hanging with Kurt Cobain.

And something like the way popes, kings and bluesmen names themselves in a lineage, the tectonic shifts that resulted in the explosion of creativity in black metal over the last decade can be traced by names. Starting with the nod to Sabbath in its name, Earth has spawned a lineage of namesakes. The band released the live album Sunn Amps and Smashed Guitars, containing a single half-hour track, in 1995. (The 2001 reissue included a bonus track with vocals by Cobain.) The album was titled in tribute to the band's favorite brand of amplifier, and it was that album which in turn gave Sunn O))), the kings of the New Wave of Downtempo Heavy Metal, its name. (Like the amp, the band name is pronounced “sun,” the “O)))” representing the sun on the amplifier logo.) And in 2001, Stephen O'Malley and Greg Anderson (of Sunn O))) and Southern Lord records) formed a band with Lee Dorian (Cathedral, Napalm Death) and Justin Greaves (Electric Wizard) called “Teeth of Lions Rule the Divine,” taking its name from a track on Earth's second record. So Earth's cred papers are clearly in order. But while the NWODHM has blossomed, Earth has turned slowly toward the dawn. After a break from recording, during which Carson worked past drug addiction, the band came back with a new and almost sunny, well, overcast anyway, sound.

The 2008 Southern Lord release The Bee Made Honey in the Lion's Skull featured the band's boldest and most unusual lineup yet. The new quartet featured Adrienne Davies on drums, Steve Moore on grand and electric pianos and Hammond organ and Don McGreevy on electric and upright bass, and even featured jazz and Americana guitarist Bill Frisell on three tracks. It may have been the furthest Carson had ever strayed from the metal roots, but it was still epic Earth: long instrumental tracks built from ploddingly slow riffs and improvised asides.

There wasn't a new release until this year's Angels of Darkness, Demons of Light 1. (The 2010 issue A Bureaucratic Desire for Extra-Capsular Extraction was a compilation of early recordings.) Angels/Demons brings Earth closer to the rock core, but by no means is it a reversal of the band's slow orbit. Davies (who has been with the band since the 2005's Hex; Or Printing in the Infernal Method, including a short stretch where she and Carson played as a duo) is the only member retained. The textural space filled by keyboards on Bee/Lion is now occupied by Lori Goldston's cello. The varying instrumentation has resulted in two of the richest records in the Earth discography, but it never seems as if the band is struggling to do something new. Reviews have tossed around labels like “jazzy” and “country,” and Carson has said the same in interviews, but it's not like the band is trying on genres for size.

Angels/Demons is a heavier record than Bee/Lion, but at the same time it's more open, even including a 20-minute wholly improvised track. The band's improvising side was on fine display when they played le Poisson Rouge in New York in June. The lineup had changed again slightly for the touring band, and with Angelina Baldoz replacing Karl Blau on electric bass Carson became the only male in his group. It is, perhaps, a demographic that shouldn't matter, or that shows another aspect of metal's changing face, or just serves to remind that when it all is up, you've got to go back to Mother Earth.

About half the slowly majestic, 90-minute set was made up of songs from the new album and included the title track from Bees/Lion. But the setlist wasn't reserved to new material: They reached back to “Ouroboros is Broken,” the first song Carson wrote for the band (and being performed, he said, for the last time) and a cover of a song by the circa 1960s British folksinger Anne Briggs. Live they were something to behold. Davies' solid, slow-motion drumming seemed like a video effect, and the intermingling of cello and guitar was resonant.

If there is something countryish, as Carson and his legion of bloggers claim, about the new Earth, it's through a filter of Neil Young, or maybe the Dirty Three. But they have something else. They are an exercise in restraint, which might just be the buzzword for the NWODHM or even, if so grand a claim might be made, for innovative music in the early 21st Century. Back in the 20th, jazz, improv, rock, they were rarely about restraint. Anton Webern’s lessons went largely unlearned. But nowadays withholding abandon is where it’s at. They weren’t without forebears; AMM, the Necks, hell, Satie as well. Then Polwechsel, Dawn of Midi, Om, Memorize the Sky and legions of others. But Earth, Earth is rock and roll. This isn’t conceptual or ironic or even strategic. It's real, dirty, rock and roll. Slow and druggy wins the race.

Monday, August 15, 2011

Thursday, August 4, 2011

Dashiki: A Jazz Mystery by Flo Wetzel

by Kurt Gottschalk

Florence Wetzel

Dashiki

iUniverse

Jazzbos have a bad habit of making things … jazzy: jazz nativities, jazz brunches, jazz hands. It's perhaps a product of the underdog psychology, a bit of defensiveness about having occupied so much more marketplace real estate 40 or 50 years ago than today, a desperate attempt to prove they can change with the times. This is relevant here only because it's so worth noting that in her “jazz mystery” Florence Wetzel has the appearances of falling into the trappings of jazz as an adjective, but wonderfully manages not to.

There are two basic things Wetzel had to do to make her jazz mystery work: One was to write a good novel about jazz and the other was to write a good mystery. Falling short of either of those would have meant running the risk of being quaint. And unfortunately, the book's title, Dashiki, and its cover, with funky font and Afro-festooned model, don't do much to convince otherwise. That the design makes sense within the context of the story only matters post-point-of-purchase.

But this is classic book-by-cover-judging, and Wetzel's too smart to err on either the jazz or the mystery count. Instead, she has crafted a story which works as a finely-tuned thriller while fitting snugly within jazz history. The double-murder in her tale involves Shinwell Johnson – a b-list trumpeter who moved in circles with Art Blakey and John Coltrane and was just beginning to have his moment some 40 years ago when he was killed – and Betty Brown, his one-time girlfriend whose current-day killing is the crux of the book. A third crime gives the tale its impetus: Brown was in possession of rare tapes of Coltrane playing with Thelonious Monk which Johnson had stolen from Trane's house. When her body was discovered, the tapes were gone.

Wetzel's deep knowledge of jazz enables her to construct a thoroughly believable story, and if it might be a bit name-droppy at times (presumably not every reader is going to follow every mention of Alfred Lion or Lee Morgan) the stripe of her fiction never clashes with the plaid of nonfiction in which she's she's placed it. Her pacing and use of foils and humor make for a fine suspense yarn. But more importantly, she gives her characters rich emotional depth and writes affectionately about the jazz geeks who populate her world, from the heroine journalist caught up in the crime to the round of acquaintances who are key to the plot's unfolding. (In full disclosure, I've known Wetzel and admired her work for years, and have a cameo role as one of those geeks.) Ultimately, it's Wetzel's gift for creating rich and empathetic characters that makes her jazz mystery such an enjoyable and unpredictable read.

Monday, August 1, 2011

Recent Recordings from Matana Roberts

Coin Coin Chapter One: Les Gens de Coleur Lebres

(Constellation)

Live in London

(Central Control)

by Kurt Gottschalk

Although she’s been working the project live for several years already, Les Gens de Coleur Lebres is the first part of Matana Roberts’ epic Coin Coin project to make it to record. The series of suites (too big to call a single work) is in 12 parts — or “chapters,” as she tags them — each a musical portrait of someone in her family history.

Chapter One, released on the Canadian label Constellation, is a smart and harrowing telling of one of the ugliest chapters in America’s own history, and perhaps more importantly of the people who survived it. The literal part of the story doesn’t come in straightaway. Roberts stretches her Montreal 12tet first, pushing them between loose jazzy themes and (more) open improvisations for the first seven minutes before introducing the first vocal piece, “Por Piti,” which confronts the listener with a harrowing pain before the scene has even been set. It then retreats into a series of mid-Coltrane-reminiscent lines before folding in a complementary vocal part by singer Gitu Jain and then the first recitation, a quick litany of the horrors seen by the protagonist, born into slavery.

Roberts has a good sense for structuring composition and improvisation into movements and guiding her bands through them, making for another sort of storytelling. The subject of slavery is certainly tough material either to write or to recite, and Roberts’ delivery comes off as a bit dated — not 1840s but 1970s. There’s a black feminist theater vibe at play in the Ntozake Shange-styled oration which could be a distraction if everything else weren’t so well done. The spoken passage is brief and is immediately swallowed up by a quick horn frenzy followed by an antebellum string lament then a taut, repeated line which proves to be the unexpected foundation of a brass band theme, oddly coupled with hard electric guitar.

The work solidifies as the ensemble moves through the gorgeous and thoughtful “Song for Eulalie” and then “Kersalia,” which includes a more successful orchestrated recitation before pulling some more near-New Orleans jazz. These are followed by the album’s masterstroke. “Libation for Mr. Brown: Bid em in...” is a clever and catchy song about a slave auction, preying on the feeling of an active, enjoyable afternoon almost to the point of deception: Sung from the point of view of the auctioneer, the sale of human beings is accompanied by the warmth of a sunny day. It’s brilliantly sing-song and plaintive, the simple melody inducing a very real fright.

Roberts doesn’t use the text to tell the whole story and the project seems to demand a box set (or flash drive, at least) release with notes telling the literal story that only comes through in glimmers in the musical telling. At the same time, however, what Coin Coin might be about is not the stories themselves but simply the fact that they exist, that they haven’t been forgotten, that Roberts has access to them as a source for inspiration. In July, Roberts premiered the sixth chapter of Coin Coin at the Jazz Gallery in New York City, this section based on 139 pieces her great grandfather using the Bible as a source for musical inspiration at the same time while at the same time teaching himself to read. Like “Papa Joe,” Roberts has a grand storyline to chart through music. Not quite a jazz opera, not quite musical theater, Roberts is crafting a new and personal form of narrative.

Live in London is a more conventional jazz outing, recorded at the Vortex by BBC radio with a crackerjack British rhythm section. They open with a 27-minute take on “My Sistr,” a song written by the Canadian singer Frankie Sparo, who also records on Constellation. Roberts’ “Pieces of We” is followed by an exciting piece called “Glass” then “Turn it Around,” a Carribean-tinged bop that morphs into a meditation in its six quick minutes. The album’s final act is dominated by a wonderfully faithful-and-free version of Duke Ellington’s “Oska T” before closing with the gentle outro “Exchange.” It’s a solid jazz record, perhaps not as important but at the same time nicely free of the intensity of Les Gens de Coleur Lebres.

Over the last decade, Roberts has made her presence known among those in the know in Chicago, New York and Montreal, and while these aren’t her first releases they still feel like an arrival for an artist who’s well worth continued watching.

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

The Sounds Around

by Brian Olewnick

Every so often, more so in recent years, a release passes across my desk and through my ears whose contents consist of unadulterated, unprocessed field recordings. Now, I have, I daresay, hundreds of recordings that utilize field recordings to one extent or another but even those wherein the entire contents are sounds picked up by a mic left out in the desert or beside a highway or within the hull of an old boat generally involve some degree of manipulation by the person involved, some sculpting, some design element. These can, in the right hands, be extraordinarily beautiful documents. I'm thinking of Toshiya Tsunoda's "Scenery of Decalcomania", for example. The choices he makes, the weight he assigns to the various elements work to create a composition which seems for all the world to be "just" a recording of a scene but, in fact, is an idealized situation, a fictional world more incisively etched than what you're likely to hear yourself, as a blank wall by Vermeer contains more in it than you're likely to see, looking straight into one.

Tom Lawrence's "Water Beetles of Pollardstown Fen" (Gruenrekorder) is a set of ten recordings of just that, as well as a good deal of plant life. All of the sounds--and there's an impressive variety of them--were recorded beneath the surface of the water, the mic often positioned quite close to the stridulating insect. The sounds are reasonably fascinating--how could they not be?--all clicks and whirs and guttural buzzes and whines, sometimes possessing an eerily human quality, like a covey of muttering old crones or some guy iterating a brief, pained cry. It's certainly a world unobtainable by ones even were one to immerse head in fen so there's a certain value having been exposed to it as all. The question is, is that value one of a purely educational or scientific sort and, if so, how to deal with it when presented as "art". There's also the issue, beautifully recorded though it may be, of how much is lost hearing these sounds issue from two speakers; if nothing else, the reality is a surround-sound experience. How to evaluate? Try as I might, I can't really rate this water scorpion's croak over that Great Diving Beetle. No reason to, of course, but after a listen or perhaps two, what does one derive from this. I now have some idea of what the insect life in this fen and, by extension, other small bodies of water, may tend to sound like which is all well and good, but am I going to go back to this to refresh my memory? In all likelihood, no. Unlike the example given above, the Tsunoda, I don't think there will be layers to continue to peel away, relationships to discover for the simple reason that there's not a human decision maker, at least not one making decisions of much import aside from track length. Or perhaps decisions were in fact made and the hand that made them lies a bit heavy, smoothing the sounds into a kind of sheet that, for all its wealth of sounds, carries with it a kind of sameness, a sameness that I very much doubt would be heard in situ, where one would be making his/her own decisions on how to listen, on how to balance the rich, subaqueous sound world. Somehow, something essential seems lost in the translation to disc, more so than is, of course, always the case with music transferal generally.

Eisuke Yanagisawa's "Ultrasonic Scapes" offers a case that is, in one sense, at an opposite end of things but in another, comes up against the same problem. He uses a bat detector to makes his recordings. One track, indeed, depicts bats while another goes after a choir of cicadas but the majority, eight out of ten cuts, pick up the faintly heard, to human ears, sounds of the industrialized world, including electric gates, street lights, muted TVs and computer innards. As with Lawrence's disc, one is privy to sound environments normally hidden from, um, view although in this case, one imagine that, given a quiet enough space and the desire to do so, one could discern a good bit of it. But again, it's presented "as is", without manipulation or intent save for determining track length. Are the sounds interesting? Sure, for the most part, all of them, I suppose. Are they more interesting than what I can hear almost any time I want by merely concentrating on what happens to be within range? I'm not so sure. Granted, bats and cicadas aren't flitting about at the moment, and the intensity level is pretty high here but I think we've all enjoyed a good refrigerator hum, savored the ultrasonics emitted when the TV is muted. I'll be on a ferry this weekend and fully intend to lean up against the engine housing, letting the dull roar vibrate ears and body. The awareness of all the sounds around us which, surely, we've all been practicing to one extent or another at least since finding out who this John Cage feller is, makes experiencing a similar set of sounds through speakers a somewhat diluted event. Not only is, unavoidably, a good bit of spatial resonance lost but, as mentioned above, one feels a bit coerced down the recordist's chosen path. It's one thing, perhaps, to be so led in the course of a composed or improvised piece of music, another when it's something apart from the person making the delivery. You'd somehow like to be introduced to an area, then let alone to discover things on your own, an impossibility, I guess, given existing technology.

This is not to say that either recording isn't worth listening to. They are, in a way (The Yanagisawa more so than the Lawrence, to these ears), even if they leave me with an extremely unsatisfied sensation. They both succeed, as near as I can do, with doing what they set out to and do so admirably and attractively but I can't shake the feeling that I'd rather dip my ear in a pond or press it up against a street lamp myself.

Gruenrekorder

Every so often, more so in recent years, a release passes across my desk and through my ears whose contents consist of unadulterated, unprocessed field recordings. Now, I have, I daresay, hundreds of recordings that utilize field recordings to one extent or another but even those wherein the entire contents are sounds picked up by a mic left out in the desert or beside a highway or within the hull of an old boat generally involve some degree of manipulation by the person involved, some sculpting, some design element. These can, in the right hands, be extraordinarily beautiful documents. I'm thinking of Toshiya Tsunoda's "Scenery of Decalcomania", for example. The choices he makes, the weight he assigns to the various elements work to create a composition which seems for all the world to be "just" a recording of a scene but, in fact, is an idealized situation, a fictional world more incisively etched than what you're likely to hear yourself, as a blank wall by Vermeer contains more in it than you're likely to see, looking straight into one.

Tom Lawrence's "Water Beetles of Pollardstown Fen" (Gruenrekorder) is a set of ten recordings of just that, as well as a good deal of plant life. All of the sounds--and there's an impressive variety of them--were recorded beneath the surface of the water, the mic often positioned quite close to the stridulating insect. The sounds are reasonably fascinating--how could they not be?--all clicks and whirs and guttural buzzes and whines, sometimes possessing an eerily human quality, like a covey of muttering old crones or some guy iterating a brief, pained cry. It's certainly a world unobtainable by ones even were one to immerse head in fen so there's a certain value having been exposed to it as all. The question is, is that value one of a purely educational or scientific sort and, if so, how to deal with it when presented as "art". There's also the issue, beautifully recorded though it may be, of how much is lost hearing these sounds issue from two speakers; if nothing else, the reality is a surround-sound experience. How to evaluate? Try as I might, I can't really rate this water scorpion's croak over that Great Diving Beetle. No reason to, of course, but after a listen or perhaps two, what does one derive from this. I now have some idea of what the insect life in this fen and, by extension, other small bodies of water, may tend to sound like which is all well and good, but am I going to go back to this to refresh my memory? In all likelihood, no. Unlike the example given above, the Tsunoda, I don't think there will be layers to continue to peel away, relationships to discover for the simple reason that there's not a human decision maker, at least not one making decisions of much import aside from track length. Or perhaps decisions were in fact made and the hand that made them lies a bit heavy, smoothing the sounds into a kind of sheet that, for all its wealth of sounds, carries with it a kind of sameness, a sameness that I very much doubt would be heard in situ, where one would be making his/her own decisions on how to listen, on how to balance the rich, subaqueous sound world. Somehow, something essential seems lost in the translation to disc, more so than is, of course, always the case with music transferal generally.

Eisuke Yanagisawa's "Ultrasonic Scapes" offers a case that is, in one sense, at an opposite end of things but in another, comes up against the same problem. He uses a bat detector to makes his recordings. One track, indeed, depicts bats while another goes after a choir of cicadas but the majority, eight out of ten cuts, pick up the faintly heard, to human ears, sounds of the industrialized world, including electric gates, street lights, muted TVs and computer innards. As with Lawrence's disc, one is privy to sound environments normally hidden from, um, view although in this case, one imagine that, given a quiet enough space and the desire to do so, one could discern a good bit of it. But again, it's presented "as is", without manipulation or intent save for determining track length. Are the sounds interesting? Sure, for the most part, all of them, I suppose. Are they more interesting than what I can hear almost any time I want by merely concentrating on what happens to be within range? I'm not so sure. Granted, bats and cicadas aren't flitting about at the moment, and the intensity level is pretty high here but I think we've all enjoyed a good refrigerator hum, savored the ultrasonics emitted when the TV is muted. I'll be on a ferry this weekend and fully intend to lean up against the engine housing, letting the dull roar vibrate ears and body. The awareness of all the sounds around us which, surely, we've all been practicing to one extent or another at least since finding out who this John Cage feller is, makes experiencing a similar set of sounds through speakers a somewhat diluted event. Not only is, unavoidably, a good bit of spatial resonance lost but, as mentioned above, one feels a bit coerced down the recordist's chosen path. It's one thing, perhaps, to be so led in the course of a composed or improvised piece of music, another when it's something apart from the person making the delivery. You'd somehow like to be introduced to an area, then let alone to discover things on your own, an impossibility, I guess, given existing technology.

This is not to say that either recording isn't worth listening to. They are, in a way (The Yanagisawa more so than the Lawrence, to these ears), even if they leave me with an extremely unsatisfied sensation. They both succeed, as near as I can do, with doing what they set out to and do so admirably and attractively but I can't shake the feeling that I'd rather dip my ear in a pond or press it up against a street lamp myself.

Gruenrekorder

Monday, July 18, 2011

Derek Bailey: More 74

Derek Bailey

More 74

(Incus)

by Kurt Gottschalk

Any discovery of a tape box with Derek Bailey’s name on it is something to be heralded. He was an unequivocal champion of improvisation as instinct, not genre (and certainly not merely “jazz”), and an absolute iconoclast on his instrument. If all artists were as intent on upending the context within which they exist, we likely wouldn’t be able to tell paintings from pantomimes.

Debilitation eventually quieted his sonic quest, and unearthed recordings have been surprisingly few since his 2005 death, but the discovery of unreleased tapes from the sessions that produced his 1974 record Lot 74 is a fantastically welcome surprise. That album — released early in his recording career (and issued on CD in 2009 by Incus, the label he co-founded) — caught him in his most overtly experimental period. Following the two volumes of Solo Guitar, Bailey set out to expand his instrument. With two leads coming off his guitar, running to separate volume pedals and separate amplifiers, he was able to create an electrified, stereo field. His utterly enigmatic plinks and clusters and harmonics and muted strings pan back and forth to dizzying effect.

He plays the “stereo electric guitar” on all but the last seven minutes of More 74, the CD issue of that discovered tape reel, and as terrific as the tracks are, they are outtakes. Many of them are under five minutes, and there is included — rather fascinatingly — a few alternate takes of tracks Lot 74. What is perhaps most wonderful about getting a fresh listen to his electric set-up, though, isn’t how radically different he sounds but how much the same. The rig allows for more exaggerated gestures, but the style is familiar, and in fact was remarkably consistent throughout his recording career. It’s as if, having heard the attack and delay and convergences of dually amplified strings, he soon returned to acoustic playing to chase those same sounds.

The final seven minutes of the disc are performed on a more curious device from Bailey’s days of axe modification, an instrument he called the “19-string (approx.) acoustic guitar.” It’s a sort of manic, harp-like thing, with constant detuning a rattling, but again sounds remarkably like him. The program closes with a track called “I Remember the Seventies,” a stab (assumedly the first) at what is called “In Joke (Take 2)” on Lot 74. Here he looks back on what was then the current day, not accompanying himself in a customary sense but playing jaggedly while speaking, as he did on his later Chats records. The piece is delivered with no undue irony, just a nice touch of absurdism, as he recalls his contemporaries in an economy of verbage. It is a happy eventuality that 37 years later, we get to remember again.

More 74

(Incus)

by Kurt Gottschalk

Any discovery of a tape box with Derek Bailey’s name on it is something to be heralded. He was an unequivocal champion of improvisation as instinct, not genre (and certainly not merely “jazz”), and an absolute iconoclast on his instrument. If all artists were as intent on upending the context within which they exist, we likely wouldn’t be able to tell paintings from pantomimes.

Debilitation eventually quieted his sonic quest, and unearthed recordings have been surprisingly few since his 2005 death, but the discovery of unreleased tapes from the sessions that produced his 1974 record Lot 74 is a fantastically welcome surprise. That album — released early in his recording career (and issued on CD in 2009 by Incus, the label he co-founded) — caught him in his most overtly experimental period. Following the two volumes of Solo Guitar, Bailey set out to expand his instrument. With two leads coming off his guitar, running to separate volume pedals and separate amplifiers, he was able to create an electrified, stereo field. His utterly enigmatic plinks and clusters and harmonics and muted strings pan back and forth to dizzying effect.

He plays the “stereo electric guitar” on all but the last seven minutes of More 74, the CD issue of that discovered tape reel, and as terrific as the tracks are, they are outtakes. Many of them are under five minutes, and there is included — rather fascinatingly — a few alternate takes of tracks Lot 74. What is perhaps most wonderful about getting a fresh listen to his electric set-up, though, isn’t how radically different he sounds but how much the same. The rig allows for more exaggerated gestures, but the style is familiar, and in fact was remarkably consistent throughout his recording career. It’s as if, having heard the attack and delay and convergences of dually amplified strings, he soon returned to acoustic playing to chase those same sounds.

The final seven minutes of the disc are performed on a more curious device from Bailey’s days of axe modification, an instrument he called the “19-string (approx.) acoustic guitar.” It’s a sort of manic, harp-like thing, with constant detuning a rattling, but again sounds remarkably like him. The program closes with a track called “I Remember the Seventies,” a stab (assumedly the first) at what is called “In Joke (Take 2)” on Lot 74. Here he looks back on what was then the current day, not accompanying himself in a customary sense but playing jaggedly while speaking, as he did on his later Chats records. The piece is delivered with no undue irony, just a nice touch of absurdism, as he recalls his contemporaries in an economy of verbage. It is a happy eventuality that 37 years later, we get to remember again.

Sunday, July 10, 2011

Michael Mantler - The Jazz Composer's Orchestra

Biographical details regarding Michael Mantler seem to be fairly scarce. Trawling about on-line, we see that he was born in Vienna in 1943, began playing trumpet at 12, worked in dance hall bands from the age of 14 and, in 1962, immigrated to the US to study at Berklee, an experience he apparently found uninspiring. He moved to New York in 1964, quickly hooking up with musicians involved in the “October Revolution in Jazz“ and, in particular, with Carla Bley, forming a personal and musical relationship that lasted until 1992. The pair formed the Jazz Composer’s Orchestra in 1964, and also the Jazz Realities Quintet which, at various times, included Steve Lacy, Peter Brötzmann, Kent Carter and Peter Kowald.

His first release, from 1965, already bore the title, “Communication” and featured a hefty collection of musicians including Archie Shepp, Steve Lacy, John Tchicai, Paul Bley, Jimmy Lyons, Roswell Rudd and more. The music shows glimmers of things to come or larger aspirations perhaps, but is more a mass of somewhat exciting, somewhat muddled improvisation, very loosely molded along vague structures. I’m not at all sure what transpired in the ensuing three years, whether or not Mantler acquired any formal training in orchestration (whether he ever had any at all, in fact, of if he was self-taught, which it sometimes sounds like), but whatever the case, by the time he was 25, his conception had matured and blossomed into an astonishing creature.

The first album under the JCOA imprint was a two-record set that arrived in a gleaming silver box bearing the simple title, “The Jazz Composer’s Orchestra”, followed by a listing of the principal soloists, Cecil Taylor’s name separated from the rest: Don Cherry, Roswell Rudd, Pharoah Sanders, Larry Coryell and Gato Barbieri. Along the bottom, read, “Music Composed and Conducted by Michael Mantler”. Inside was a 12 x 12” booklet bearing track information, photos, scores, an excerpt from Beckett’s “How It Is”, a two-page poem by Taylor and texts by Paul Haines and Timothy Marquand. The pieces once again, with one exception (“Preview”), bore the title, “Communications”, here numbered 8 through 11. Looking at the instrumentation, we still see what is essentially a jazz big band, larger than the prior recording (over 20 musicians) and notable for the presence of five bassists. The sound generated, however, was orchestral.

It was a wonderful idea, one borne partly of the time but not really followed through anywhere else to the degree heard here, much less with similar success: Compose works for a band of extremely talented musicians that fused a kind of dark, brooding Romanticism, as though Arnold Böcklin’s vision was filtered through Mahler by way of Beckett, all exposed to the protean strength and creativity of 60s free jazz. Within this dense mix, position soloists whose voices emerge from the roiling darkness as brilliantly faceted jewels, unleashed from the group but gravitationally pulled back into it. Add to this the serendipity of the chosen soloists being at or near the height of their powers and you have the recipe for one incredible stew.

An obvious key to the success of these works is the dense, sprawling orchestration that Mantler laid down behind the soloists—“behind” isn’t the correct term as the music writhes and gropes, sending out thick tendrils that envelop the featured musicians, never allowing things to atrophy into a soloist/accompaniment form, but keeping things, for lack of a better term, extraordinarily organic and plastic. As the first track, “Communications #8” begins, the orchestra wells up, already seething, sounding somehow more “orchestral” than jazz-bandish despite the instrumentation (the massed basses might be a contributory factor). Mantler’s score-notes for the piece: “For a team of players. Loosely strung. Much singing. Release. A long descent.” The long, brooding tones are routinely disrupted by more staccato passages, Bley’s spiky piano ameliorating any smooth flow, the whole jittery and dark before Cherry’s clarion pocket trumpet enters. Cherry, in the late 60s, to these ears, reached an astonishing peak of melodic inventiveness, doubtless inspired by his absorption of Eastern musics, though transformed into something very unique (see: “Eternal Rhythm”). He negotiates a path through the maze of strings and horns, graceful but not a little tragic. Again, crucially, he’s on equal footing, not in front of the orchestra but within, a single mass. Then the fire-breathing Barbieri enters, full force, ripping through his tenor, himself having entered a period of unfettered creativity that would carry through to “Escalator Over the Hill” and “Tropic Appetites” before fame and final tangos ensnared him. But he’s so strong here, soon entwining with Cherry, plaintive and vital Cherry, forming a complex vine of sound, whirling through the arrangement, the tubas and French horns darkly billowing, Cyrille driving the ensemble with abandon. And the long, not unruffled descent.

“Communication #9” (“About the weaving of clusters. The natural electric orchestra. The amplifier.”), oddly enough, might be the “weakest” piece here at the same time as it could be the finest thing Coryell ever recorded. I remember reading an interview with Coryell a long while back wherein he expressed his frustration that every time he’d make what he thought was a significant advance in pushing forward the possibilities of the electric guitar, he’d soon find out that Hendrix had beaten him by a few months. Well, here in May of ’68, he’s certainly pressing at boundaries, at least those walls set up in the galaxy apart from Rowe and Bailey. The orchestration is sparer, piano and high string harmonics supporting quietly harsh brass that feed directly into the initial feedback-laden guitar. Photos from the session show Coryell engaged in a wrestling match, his guitar vs. the amp; perhaps half of his time here is spent wringing feedback from his axe, a bit more up front than were Cherry and Barbieri, and maybe indulging, in this context, in a tad more flashy playing than necessary, but nonetheless impressive.

Steve Swallow’s gorgeous, questioning bass introduces “Communications #10” (“Expansion. The exquisite low horn”), worth the price of entry on its own, before the elegiac reeds and brass, evocative of some of Carla Bley’s writing, usher in the body of the piece, again laying a substantial bed, open to and full of possibilities from which the featured player emerges, here Roswell Rudd, his natural buoyancy spiced with no small amount of mordancy and even the tinge of despair. Beckett is never far from Mantler’s conception.

“to have done then at last with all that last scraps very last when the panting stops and this voice to

have done with this voice namely this life.”

Rudd trends toward his horn’s lower reaches, bringing forth guttural shouts from the surly orchestral growls. As with the others, it’s difficult to think of a finer, more expansive performance from him, as though Mantler had provided exactly the right framework and accompaniment, especially Beaver Harris here, on drums.

And then there’s “Preview”, a 3:23 blast furnace attack with white hot slag erupting from the bell of Pharoah Sanders’ tenor over the incessant, almost martial throb of the orchestra. No let up, start to finish, one of the mostly densely packed, insanely ecstatic performances on record, something guaranteed to send the neighbors fleeing in alarm. Has Sanders ever sounded this volcanic elsewhere? Is there another example where concision and raw power are so perfectly combined? An exhausting, astonishing work.

And, really, it proves to be only a stage-setter, an appetizer for what follows: about 33 minutes, in two sections, of some of the music incredibly inventive and dynamic Cecil Taylor playing ever caught on record, “Communications #11”. (“From the association with one man. The orchestration of his piano.”) I remember reading the review of this piece in downbeat, the writer explaining that he felt the need to glance over at his stereo to ensure that the LP wasn’t levitating off the turntable. It really is that strong, protean, a living, throbbing, hyper-imaginative set of music with the wonderful happenstance of Mantler’s ideas blossoming at the exact moment Taylor was making the transition in his playing from the fevered hermetics of his two mid-60s masterpieces, “Unit Structures” and “Conquistador!” into the elaborate and expansive explorations that would soon be heard in works like “Indent” and “Silent Tongues”. Trying to describe it is something of a fool’s errand anyway; I’ve often had the mental image of a cauldron containing molten metal, boiling, sustaining a plosive pattern somewhere between regularity and chaos. Unlike many a “pairing” between Taylor and a playing companion where the pianist all but overwhelms his ostensible partner, the orchestra gives as good as it gets, spurring him outward. It’s an avant piano concerto that indeed nods back to a kind of Mahlerian tonality while giving Taylor free rein to pull it toward the 21st century. An utterly breathtaking work, successful on multiple counts and a high water mark in Taylor’s career.

At least that’s my take on it; one wonders about Mantler’s. He never really broached this area again, with the arguable exception of his monolithic and extremely impressive “13” from 1975, which shared an LP with Bley’s beguiling and lovely “3/4”, itself a piano concerto of sorts but in a far lighter vein. Otherwise, he tended to work with smaller ensembles, early on notching a couple of outstanding one-offs, “No Answer”, a setting of Beckett text with Cherry, Bley and Jack Bruce and “The Hapless Child”, a prog-rockish rendition of several Edward Gorey poems featuring Robert Wyatt, Terje Rypdal and others. He continued to utilize Beckett and like-minded writers and his work became even bleaker, often intriguing but, to these ears, lacking that unique combination of latent Romanticism to leaven the dourness; there was no Cecil Taylor to provide the ecstatic leaps from the muck. If anyone picked up the torch, one would have to cite Barry Guy with his London Jazz Composer’s Orchestra, albeit with a necessarily different personal tinge and, arguably, a level of soloist one tier below these fellows here (while still excellent).

Yet I don’t hear this recording, this set of “Communications”, discussed very often and think it’s a shame. For this listener, it stands as one of the very finest creations of the 60s jazz avant garde and deserves far wider recognition.

--Brian Olewnick

--Brian Olewnick

Monday, July 4, 2011

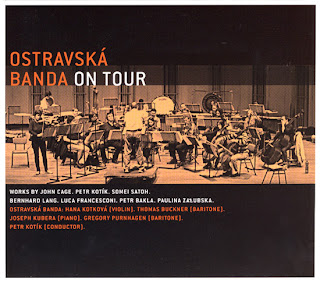

Ostravská Banda: On Tour

Ostravská Banda

On Tour

(Mutable)

by Kurt Gottschalk

The versatile 20-piece Ostravská Banda might be seen as a cultural-ambassador assembly for the biennial Ostravská Days festival, a growing part of the Czech Republic's new music landscape. Initiated in 2001, the festival is dedicated to contemporary orchestral works. In 2005, the Banda was founded by SEM Ensemble conductor Peter Kotik to give the festival its own standing orchestra and to create a touring body to represent the work.

The seven compositions presented over the two hours of the double CD On Tour were recorded in 2010 at appearances in Poland, Austria, the Netherlands and the Czech Republic. The program represents some pillars of 20th Century composition as well as – can we call it post-20th Century music, the patron saint being, unsurprisingly, John Cage, and the ensemble presents a challenging reading of his Concert for Piano and Orchestra. The piece comes with a Czech footnote: While it allows for variable instrumentation, it was only in Prague in 1964 that he was able to give the first full presentation of the piece following its 1958 New York premiere. The piece is constructed (as is true with so many of Cage's works) in time intervals, with allowable events for individual instruments – scored or suggested sounds – happening within the time brackets. The featured pianist is given the most complex part, with a book of 64 one-page scores from which to choose.

With the talented American pianist Jospeph Kubera at the fore, the piece is given a dramatically disparate performance – appropriate for the work, even if it is surprising give the fullness of the rest of the tracks. Musical gestures don't fall together, they just occur, as famously is the composers intention. The orchestra recedes to the background as the piano – bright and abrupt – dominates the soundspace. The noncohesivesness becomes a richness in field over its 23 minutes, something the composer no doubt would have appreciated.

That piece starts off the second disc of the set, and is followed by Kotik's 2009 composition In Four Parts [3, 6 & 11] for John Cage. It's a tightly constructed homage to the earlier composer's first love, percussion music, and is a taut and dynamic 24 minutes – so much so that it leaves Bernhard Lang's 2008 percussion piece Monadologie IV in its shadow. As opposed to the rigors of Kotik's piece, the Monadologie comes off as a sort of exploded drum solo, that is, more showy than satisfying. Thirty-six minutes of percussion music might be a bit much for some listeners, and it does make for a diminished finale.

The first half of the set opens with a wonderfully romantic flourish. Luca Francesconi's 1991 Riti Neurali follows (as the liner notes point out) the instrumentation of Schubert's Octet in F Major, although it speaks in the dramaturgy of Schoenberg; The violin-dominated flurry is exhilarating. While Francesconi studied under both Berio and Stockhausen, here he speaks in a language of measured atonality and straightforward passion.

That piece is followed by two works by young composers, both vivid and exciting, and quite different from one another. The 31-year-old Petr Balka's Serenade is a wonderful construction of differing tonal qualities. Bold outbursts are laid over quieter and sometimes fairly simplistic phrases in unexpected ways, creating a tableau of phrases with the energy of potentiality, of what the composer calls “not-quite-yet-music.” The 27-year-old Polish composer Paulina Zalubzka works with varieties of lyricism reminiscent in ways of both the Francesconi and Bakla pieces in her Dispersion, its persistent rhythm moving in and out over unabashedly beautiful passages.

The only non-Western composer present here is the Japanese Somei Satoh, represented by a half-hour “reduced setting” of his The Passion. With inventive use of a male choir and strong performances from baritones Thomas Buckner and Gregory Purnhagen. The piece is just beautiful, an unusual juxtaposition of minimalist gesture and rich harmony.

The impetus behind producing such a strong and varied package as On Tour may or may not have been to serve as a calling card for the ensemble and, by extension, the festival. But either way, the point is well made.

Thursday, June 30, 2011

Nels Cline / Marc Ribot at (le) Poisson Rouge

by Kurt Gottschalk

photo by Peter Gannushkin

The pairing of Nels Cline and Marc Ribot was such a perfect prospect that it almost seemed bound to fail. Each of the guitarists is so enigmatic that their first meeting onstage — at Poisson Rouge in Manhattan’s West Village on June 15 — was easy to anticipate but difficult to prognosticate. The meeting was even seen as significant enough that what could have been a concert preview became a Downbeat cover story.

The two guitarists move in similar circles but are quite different. The difference might be summed up by saying that while Cline can play anything, Ribot can play anywhere. Cline is a chameleon who can find a place whether he’s playing with the rock band Wilco or out improvisors such as Andrea Parkins or Gregg Bendian, or backing Yoko Ono or painter Norman Wisdom. In the Downbeat story he’s even quoted as saying “I don’t want to have a style ... I’ll do whatever it takes to communicate the essence of the song.”

Ribot is no less versatile but always immediately recognizable. Whether playing with Laurie Anderson or John Zorn or as a sideman or leader for any number of groups, his sharply rhythmic playing is unmistakeable. That they’re both supremely talented and adept at working in varieties of settings was never the question. But with so much that they might do, it was hard to imagine what they actually would.

They began a set that would run close to 90 minutes at a natural starting point, Ribot leaning toward rhythm and Cline toward melodic runs, and worked toward a common ground that found both pulling Ayleresque lines off the necks of their acoustic guitars.

They brought the first piece to a close in short time and then started an easy blues with Cline playing slide. It was quickly taken over, however, by a spritely melody, blue turned to spring green. From there they built a bass heavy riff that morphed into unplugged skronk, each section lasting less than two minutes. Surprisingly, perhaps, it was the blues foundation that freed them to explore. Both gentlemanly, each always complementing the other, they shared a conviction to keep moving without pushing too hard.

Having covered considerable stylistic ground in the first two pieces and first quarter hour, they relaxed into what they had newly made their own. On the next piece, Cline played harplike repetitions over Ribot’s jagged lines, building to more slide work from Cline as Ribot pounded a bass line. For a third piece Cline prepped his guitar strings and they played a fragmented Tin Pan Alley that incorporated a bit of flamenco and other, less explicable gestures.

When they switched to electric (Ribot playing a hollowbody Gibson, Cline on a lap steel played with a bow) they created a mountainous noise that moved almost unfathomably into a crowded groove. Cline took over with his electronic effects pushing into an electric abstract Americana. Ribot sang “Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie” over a quiet squall before then made their way back to a distorted Ayleressence. The magic was borne of their knowing that they didn’t have to stay in one place, nor did they have to rush anywhere.

Monday, June 27, 2011

Suoni Per Il Popolo, June 15-25, Montreal

by Mike Chamberlain

I have been thinking about music recently in light of remarks by Erdem Helvacioglu and Satoko Fujii, two musicians for whom I have nothing but the highest respect as musicians, thinkers, and human beings. The questions have to do with categories, how we label music, how we talk about and what we expect from the music we listen to. Helvacioglu, in an interview we did in New York in April, talked about how he wanted to validate beauty in avant-garde music. The avant-garde has concerned itself in large part, Helvacioglu was saying, in terms of dealing with expressions of the negative and ugly in life., and he, who self-identifies as an avant-garde musician, is putting “beautiful sounds” (my quotation marks) in his own cinematically-inspired electronic music. Fujii, a pianist and composer whose list of recordings and collaborations is totally astonishing both for stylistic breadth and sheer output, after a concert at the Sala Rossa in Montreal during the recently-concluded Suoni Per Il Popolo that could fairly be described as beautiful in its various aspects, asked if I thought there was such a thing as jazz—Fujii questioning her own position within and among the categories of jazz and avant-garde music.

What is jazz? is the oldest and most boring question around, but discussions about the meaning of the term go far beyond mere definition. It’s interesting to me that rock fans don’t obsess over the meaning of the term rock, at least not nearly to the same extent that jazz fans and music geeks do with the term jazz.

Part of it is due to the fact that rock is much more secure as an industry and a place for musicians to make money. The Beatles, the death of John Coltrane, and the schism wrought by Miles’ going electric killed off jazz as part of mainstream culture. Wynton Marsalis came along in the early 80s and attempted to “save” jazz by taking possession of the term, defining it as a philosophy wedded to a certain set of sounds, a definition that devalued experimentation in jazz. This wouldn’t have been such a problem if no one had paid attention to Marsalis, but when he became the most public voice of jazz, his ideas about the music helped to shape the definition of jazz in the public mind, or those who were still paying attention, and in the minds of people like festival programmers. There isn’t much money in jazz (Fujii and her husband, the trumpeter Natsuki Tamura, rode the “magic bus” from Toronto to Montreal for $10 on their way to play the Suoni Per Il Popolo. I don’t think that Stevie Wonder and his entourage came anything but first class to play a free outdoor show at Montreal’s big jazz festival, the FIJM, last year), and jazz is simply not found much in the general public’s daily lived experience. But although there’s less money in jazz, the term itself is sold by festivals and venues around the world, and there is much discussion among we self- or otherwise appointed music commentators about how the marketing aspect of the term becomes at least equally as important as to how the festivals work to promote the careers and help to further the music that could be labeled as jazz.

I’m not a purist. I saw Patti Smith and Elvis Costello each for the first time at the Montreal jazz festival— and many others who are not jazz artists. It doesn’t bother me that the Montreal jazz festival presents a lot of music that no one in his right mind would call jazz. First, I don’t listen only to jazz, so I’m pleased any time the programmers book an artist or group I am interested in seeing live, no matter what they’re playing. Second, I buy the argument that the festival makes about how the bigger concerts, by artists like Patti Smith, Elvis Costello, Robert Plant, Sting, and Prince, help to pay for the artists who don’t produce as much money at the box office.

But there’s a problem. The pool of “big name” jazz artists who headline at the FIJM is aging and going on to the great jazz band in the sky. Perennials Dave Brubeck and Tony Bennett are performing in Montreal this week, and not to be too disrespectful to either of those men, one wonders if the pair have more than 10 or 12 more FIJM appearances in them—put together, of course. The problem has to do with what the festival has done or not done over the years to renew its jazz content, and to pay attention or give opportunities to some artists whose music is considered to be “too” avant-garde. Why has Anthony Braxton, for example, never been invited to do an invitation series at the FIJM? It’s a no-brainer. Of course, I grant that it might not be possible to arrange such a series easily, given personal and business considerations on both sides, but assuming some kind of mutual willingness, it seems that the set of concerts would benefit both Braxton and the festival. And there is an audience for such endeavours. But people like Andre Menard and Laurent Saulnier, who book Montreal, seem to either not see it or not want it. Case in point: virtually the only artists from Chicago who ever play Montreal are Kurt Elling and Patricia Barber. Nary a Ken Vandermark, a Von Freeman, or a Nicole Mitchell in sight at the Montreal festival, to name just a few. The so-called avant-garde jazz that is included in the festival is basically a token. The John Zorn double concert last year is the exception, not the rule. There is no real commitment to making a prominent place for the tradition of experimentation in jazz, unlike, say, at the Vancouver jazz festival.

Fortunately, we in Montreal are well-served by a smaller but in ways more vital festival, the Suoni Per Il Popolo, held at the Casa del Popolo, Sala Rossa, and associated venues in the first three weeks in June. (This year, the Suoni finished the same weekend that the FIJM kicked off.) The Suoni’s name invokes people, not a musical category, and in its eclecticism and DIY spirit reflects the sensibility, along with relatively cheap rents, that has made Montreal fertile ground for artists of all descriptions.

Since Mauro Pezzente and Kiv Stimac opened the Casa del Popolo in September 2000, avant-garde jazz has been a feature of the programming during the regular season as well as the Suoni itself, alongside electronic, noise, musique actuelle, folk, rock, cabaret, spoken word, and so on. They have built a small empire on the upper end of St-Laurent Boulevard that for some years now has included the gorgeous Sala Rossa on the understanding that the constituencies for the various music overlap in this city, and more important, on the ethos that creativity comes from the margins, and this year’s Suoni program included the likes of Omar Souleyman, Martin Tetreault, Borbetomagus, Malcolm Goldstein, the Shalabi Effect, and Keiji Haino as well as Charles Gayle, David S. Ware, Satoko Fujii’s Ma-do, Farmers By Nature, the Full Blast Trio, Atomic, and The Thing. This eclecticism and commitment to the avant-garde is the rule, not the exception, at the Casa/Sala/Suoni.

Of the concerts I attended, I was impressed, as always, by turntablist Martin Tetreault’s inventiveness and wit as he trawls the cultural landscape for materials for his constructions. His duo with David LaFrance, a member of Tetreault’s Quatour Tournedisques, was inspired by recent prophecies of the Apocalypse; he billed it as music for before, during, and after the end of the world, a 40-minute piece that delightfully blended electronics and snippets of music and radio broadcasts that carried the listener through dread and destruction to pastoral.

Fujii’s Ma-do is a quartet comprised of Fujii, Tamura, bassist Notikatsu Koreyasu, and drummer Akita Horitoshi. Delicacy, aggression, beauty, and power all have a place in the sensitive interplay of the quartet. The first set was exploratory and tentative, but the quartet opened things up on the second set, Tamura—surely the most underrated trumpeter in jazz—showing his incredible range, the quartet deferring resolution until the tension would resolve in a burst of aggression or joyous swing.

David S. Ware played a solo set in which he did two long improvisations, one on tenor, one on sopranino. He put out bursts of single-note lines in a performance that I found more rigorous than engaging. I was only able to catch Farmers By Nature’s first set, and again, the trio seemed to spend much of the 45 minutes searching for the “it” that improvisers seek. I found much to like, especially in Craig Taborn’s provocative note placements, but I didn’t find enough moments of clarity to suit my taste. The second set, from what I was told later, was much more satisfying in this regard.

I have seen The Thing three times. Each performance was different. And each was impressive for its beauty, power, and inventiveness, whether they were crushing Sixties’ soul and R’n B, freaking energy music, or as in this concert, engaging in improvisations that included a version of “Summertime” that re-imagined the piece to evoke not a southern pastoral lament but the summertime energy of a big-city and a section of “A Love Supreme.” Mats Gustafsson and Joe McPhee challenged one another, bassist Ingebrigt Hacker-Flauten and drummer Paal Nilssen-Love (my favorite drummer this side of Hamid Drake) churning out funky swing, turning time on a dime when the moment called for it.

In all of this, there was a commitment to creativity, to inventiveness, to a bricolage of the 90-year history of jazz and the popular musics that are now a part of the common musical vernacular. Beauty? Yes. Jazz? Most assuredly.

Friday, June 24, 2011

Pretentious Music is Pretentious

by Kurt Gottschalk

I recently had someone comment on the playlist for my radio show that something I was playing was so pretentious he was going to turn it off. In fact, he made a point of saying that he did not pledge to my show during the WFMU marathon because I play this sort of thing. And in general, this is totally fine by me. Nobody should like everything, and I realize that much of what I play will appeal to a small minority of people. I do, however, find it odd when someone feels their objections must be heard publicly. We revel together but object to separate ourselves from the pack. But I’m not sure why people need to announce that they’re leaving the pack. Perhaps to make it clear that they are superior to the rest, and not the other way around.

All of that is par for the course for freeform radio, for non-mainstream media or unusual artistic expression. But reading the listener’s comment I got hung up (as I often do) on a word. “Pretentious.” It’s a word I used a lot in high school. It was what we punks stood against in the battle of the “P” factions: punk vs pretension, punk vs pomposity, punks vs posers. It was clear. It was wrong. It was, it meant — I found myself at a loss. It meant being something other than genuine. Didn’t it? And punk was all about dying your hair and being yourself. It was, I reasoned, the same word root as “pretend.” The implication is usually “putting on airs of intellectualism,” or more simply “acting smarter than you are.”

If my assumptive leaps aren’t too huge, the argument then is that the music I played on the radio that afternoon was the direct result of someone acting as if they were smarter that they really are. There may be other syntactical paths to take, but it seems clear in any event that art itself can’t really be pretentious and that the accusation is actually lobbed at the artist. At which point, it seems pretty untenable. We can’t know that an artist is being true to himself or herself without knowing them personally, and if we knew them personally surely we would make the claim about them, not their work. “I can’t stand listening to Paul Simon,” for example. “I met him at a cinematographer’s party and he was so pretentious!” Is Paul Simon’s music pretentious because he’s not actually South African or Brazillian? Is it less so (or for that matter all the more so) because he often hires musicians native to the land he’s emulating? Or is it he who is pretentious for making the records? I don’t find Paul Simon to be pretentious. He strikes me as refreshingly genuine, although I’ve never met him. But clearly one could find him pretentious. Taken apart, though, the claim that his music — any music — is pretentious is, at least to me, befuddling.

So let’s assume my playlist commenter meant to say that the artists were pretentious for making a work that, well, that sounded as if it were made by someone smarter than they really were. What does that sound like? My intention here isn’t to ridicule the commenter into a corner. I got stuck on it for precisely the reason that it was something I had said many times in the past myself. We punks hated bands like Genesis and Yes because they were so “pretentious.” And I find now that I didn’t know what I meant when I said it.

The word itself comes from the Latin “praetendere,” literally “to stretch in front of,” like a curtain. So pretentious music, perhaps, is stretched in front of the artist, hiding their true identity as a regular person. In that regard, it would seem that masked performers such as Kiss, The Residents, MF Doom or Slipknot are really the pretentious ones, and that may be right. But the semantics now are clouding the issue. For what someone really means when they call an artist or their work “pretentious” is, simply, that they don’t like it and, more importantly, that they don’t approve.

Essentially what the accusation does is set up a dichotomy — “pretentious” music as opposed to “nonpretentious” music — and uses the language to make it clear which of the two classes we should prefer. This is a common and cowardly approach in discussing art. It’s not a statement of quality, it’s a simple matter of categorization. Another example will help to illustrate.

Last fall, I was asked to speak on a panel held by the Jazz Journalists Association. In the endless endeavor of critic list-making, the panel was to consider the best records of the year so far. As I’ve written elsewhere, I object to the notion of besties lists, but I’m certainly able to talk about records I like and why I like them. Since I didn’t have personal bests to select from, I brought records that I loved and which I thought might not be as well known and might spur interesting discussion. One of my favorite records from 2010 was the Trondheim Jazz Orchestra’s Stems and Cages, a project of the Norwegian city of Trondheim, which commissions different artists to assemble and lead versions of the band. Since the town is hiring someone to assemble a jazz orchestra, and the artist hired is presumably doing so in good faith, it seemed to me fair game to consider the music as “jazz” and to take it as a legitimate starting point.

The audience, and one gentleman in particular, objected vehemently. It was not jazz, they said. I asked why not, and the gentleman most vehement responded sternly that “it wasn’t based in the blues.” Really? Are we still hung up on that? I asked if all of Eric Dolphy’s music was based in the blues and he insisted that it was.

What he was doing, just like my playlist commenter, was creating a linguistic foil in order to exclude a piece of work from the class that is considered acceptable.

A third example: A friend once objected, after seeing a performance piece where a man dressed as a chef simulated sexual intercourse with a side of beef, that it “wasn’t art.” Sure it was art. If it wasn’t art, it was real, in which case we should really be worried.

What she meant to say was that it was bad art. What the vehement gentleman meant to say was that it was bad jazz. What the playlist commenter meant to say was that it was bad music. But saying that would mean making a claim that would have to be defended. If you say something is bad, you have to be prepared to defend it. If you say something is simply not what it’s presented as, then the discussion’s over. It’s not in the club. Case closed. There’s nothing to defend.

Which, really, is a pretty pretentious argument to make.

Monday, June 20, 2011

Cornelius Cardew’s “Treatise”

Cornelius Cardew’s “Treatise”

by Brian Olewnick

Cornelius Cardew’s Treatise (1963-1968) has become, in some circles, the pre-eminent graphic score of 20th century avant-garde music. Particularly among those musicians and listeners who value improvisation, it seems to have nudged aside works like Cage’s Atlas Eclipticalis or Brown’s Four Systems as the go-to score, in part or whole. Spanning 193 pages, with absolutely no written instructions (though the double line of octaves running along the bottom of each page at least suggests that the interpretation flow along musical lines, it has indeed been danced to), it consists of an enormous wealth of calligraphic richness: numbers, isolated musical signs, arcs, circles, squares, squiggles, quasi-representational figures and, most of all, lines, all rendered with a dazzling degree of elegance. A central spine (Cardew referred to the work as “a vertebrate”) runs through the work at mid-page, with occasional interruptions, anchoring it.

Cardew brought together musicians to perform the work, in whole or part, numerous times while it was gestating but after his conversion to a particularly orthodox version of Maoism around 1971, he renounced it along with all of his other prior compositions as bourgeois artifacts, effete pieces that did nothing to elevate the worker. For quite a while, it seemed to have gone into hibernation apart from often being included in performances by AMM after Cardew’s death in 1981. Keith Rowe had participated in many a realization of the piece, developing his own translation of image groups therein, and it served as a touchstone for him, perfectly melding the worlds of free improvisation and post- Cagean music. AMM would only play a handful of the pages at a time, Rowe believing that a proper, considered reading would devote six to ten minutes per page.

Ironically, it was an exceedingly rapid version of “Treatise,” led by Art Lange in 1999 (hat [now] ART 2-122) that brought the work back into the public forum. Lasting a mere 140 minutes (or about 44 seconds per page), it was necessarily a rush job and hardly scratched the surface of the piece. Rowe continued to champion it, however, playing excerpts in concert and talking about it with some constancy. Soon, Treatise became something of a staple among the burgeoning eai group of musicians and listeners, discussed and analyzed frequently and seemingly performed, in one manner or another, every other week.

Two recent renditions have surfaced, one a reading of four pages, one in its entirety, that approach the piece from distinctly different vantages, the first “traditional”, the second, not so…

Choi Joonyong, Hong Chulki, Jin Sangtae and Ryu Hankil are four of the leading improvisers in South Korea, having released a slew of impressive recordings over the last five or six years, ranging from ultra-quiet to extremely harsh sound ranges, generally incorporating low-fi devices including turntables, CD players, film projectors and assorted “broken” electronics. For this performance, they chose four pages, 20-23, and imposed a 40-minute time limit on themselves, by design or intuition coming close to that Roweian standard. I think it’s fair to say that the sounds generated bear no obvious correlation to the score (there’s a projection on the rear wall, but the musicians don’t look that way, instead occasionally—not always—peering down at their tables at individual sheets of the score there), something that’s likely quite common in realizations of Treatise. One doesn’t know how the graphics were read only that the resultant music was somehow molded into something different than it would have been otherwise. While they don’t seem to be terribly conscious of each other, certainly not reacting directly to what one another is playing, they do manage to come to mutual halts on a few occasions and cohesive ensemble formations on others. But, in the AMM tradition, they seem to respond to the totality of the room, the performance of four pages of Treatise inside it being just one element occurring at the time. Some twelve minutes in, a sustained drone is developed, possibly reflecting the omnipresent spine of Treatise that bisects almost every page, but these musicians have short patience with any kind of stasis and that drone is summarily interrupted by the clatter of tin cans and shards of static and abruptly brought to a halt, Hong and Choi standing up and entering a rear room, the latter banging something twice, clearly, the former possibly setting into motion some small toys. The set continues in this staggered, irregular, harsh fashion, the sounds of metallic clatter or a table being pushed across the floor or Hong leaving the space entirely to sound the horn on a car parked outside as likely as the more “routine” sounds of cracked electronics or screeching (recordless) turntable. It seems at a far remove from the elegant calligraphics of Cardew, the graceful arches on p. 22 or the ascending cascade of “f” shapes on p. 24. But that, of course is to look at things visually, not necessarily ascribing another kind of meaning to the shapes, lines and numbers. There’s a brief shot of p. 24 on Choi’s table and one can glimpse a dense concentration of markings he’s made thereon, so you realize that something is afoot. But that’s one of the essential beauties of Treatise: its utter openness to interpretation. Here, this listener ultimately became absorbed in the goings-on, rapt in the appreciation of the unique sound-world created via this singular model. But are there “wrong” readings?

Shawn Feeney (in a work realized in 2002, though uploaded only recently) took an entirely other approach, treating Cardew’s work as an explicitly graphic piece, devoid of intuitive meaning, removing (apart from the initial idea) any human interpretation at all. He first arranged the 193 pages to scroll across the screen from right to left, a beautiful enough image and, really, how Treatise should be viewed if at all possible, making more apparent the thoroughgoing structure of the composition. He then programmed a sine wave generator to activate upon encountering any morsel of black ink as that portion passed an invisible y-axis midway on the screen. Tones grew higher above the central spine, lower beneath it. There might be more to it with regard to specific pitches, quavers, etc., but that’s it in a nutshell. Feeney essentially sets it in motion, then stands back and watches/listens to what unfurls. It’s necessarily lacking in many of the prime elements that have been part and parcel of, I imagine, virtually every prior performance of the work: the consideration of the musician(s) involved, what they bring to the shapes and symbols they encounter, how they process them. This could easily, it seems, lead to a sterile, “science experiment” kind of enterprise but somehow that doesn’t happen, at least to these ears. Instead, several aspects emerge. One is a rather surprising sense of narrative and even drama. If you’re at all familiar with the score, you can’t help but anticipate what’s going to happen when certain standout pages enter the arena—the baroque apparatus on p. 183, for instance, or the series of large, black circular shapes on pp. 130-135. You have a couple of inches of “lead time” as the score enters the screen on the right, constantly refreshing your expectations. Another, more salient result is that, by virtue of the laser-like precision of the sine tones, you gain a greater appreciation of the microstructures within Treatise and how they relate to medium-level and larger superstructures: the risings and fallings, the contrast between smooth and rough shapes, solid and open, intensely intricate and expansively sparse. It’s one thing to view this enormous array of figures, another to have their orientation and relationships explicated, even to this fairly minimal degree, by sound. The central spine becomes quite prominent and all but unwavering (though when Cardew chooses to draw it by hand instead of rule on pp. 169-170, it’s wonderful to hear the bumpiness), causing distress in some listeners but, for myself…well, it is a vertebrate, after all. Indeed it is and that nerve column does hold things together and, I think deserves its recognition.

By consciously putting aside the entire area where, arguably, the deepest and most absorbing investigations of “Treatise” are likely to be found, Feeney has succeeded in shedding substantial light on aspects of it that are too often overlooked. In my limited discussion with other musicians and listeners, this has caused large divisions with most, I think it’s fair to say, coming down against it, finding it too formulaic and literal-minded. I can’t help but disagree while acknowledging its severe limitations. I think of it more like a scanning electron microscope photo of an object. That same object, limned by an artist able to bring the wealth of his and others’ experience to it, to imbue it with ideas, may well provide the greatest “value”. But the microscope, inhuman as it is, provides a kind of information inaccessible to one’s eyes. To these ears, Feeney’s thus made a significant contribution to the anatomy and history of this almost 50-year old work, a piece—a creature-- that, one suspects, has only begun to reveal its richness.

by Brian Olewnick

Cornelius Cardew’s Treatise (1963-1968) has become, in some circles, the pre-eminent graphic score of 20th century avant-garde music. Particularly among those musicians and listeners who value improvisation, it seems to have nudged aside works like Cage’s Atlas Eclipticalis or Brown’s Four Systems as the go-to score, in part or whole. Spanning 193 pages, with absolutely no written instructions (though the double line of octaves running along the bottom of each page at least suggests that the interpretation flow along musical lines, it has indeed been danced to), it consists of an enormous wealth of calligraphic richness: numbers, isolated musical signs, arcs, circles, squares, squiggles, quasi-representational figures and, most of all, lines, all rendered with a dazzling degree of elegance. A central spine (Cardew referred to the work as “a vertebrate”) runs through the work at mid-page, with occasional interruptions, anchoring it.

Cardew brought together musicians to perform the work, in whole or part, numerous times while it was gestating but after his conversion to a particularly orthodox version of Maoism around 1971, he renounced it along with all of his other prior compositions as bourgeois artifacts, effete pieces that did nothing to elevate the worker. For quite a while, it seemed to have gone into hibernation apart from often being included in performances by AMM after Cardew’s death in 1981. Keith Rowe had participated in many a realization of the piece, developing his own translation of image groups therein, and it served as a touchstone for him, perfectly melding the worlds of free improvisation and post- Cagean music. AMM would only play a handful of the pages at a time, Rowe believing that a proper, considered reading would devote six to ten minutes per page.

Ironically, it was an exceedingly rapid version of “Treatise,” led by Art Lange in 1999 (hat [now] ART 2-122) that brought the work back into the public forum. Lasting a mere 140 minutes (or about 44 seconds per page), it was necessarily a rush job and hardly scratched the surface of the piece. Rowe continued to champion it, however, playing excerpts in concert and talking about it with some constancy. Soon, Treatise became something of a staple among the burgeoning eai group of musicians and listeners, discussed and analyzed frequently and seemingly performed, in one manner or another, every other week.

Two recent renditions have surfaced, one a reading of four pages, one in its entirety, that approach the piece from distinctly different vantages, the first “traditional”, the second, not so…